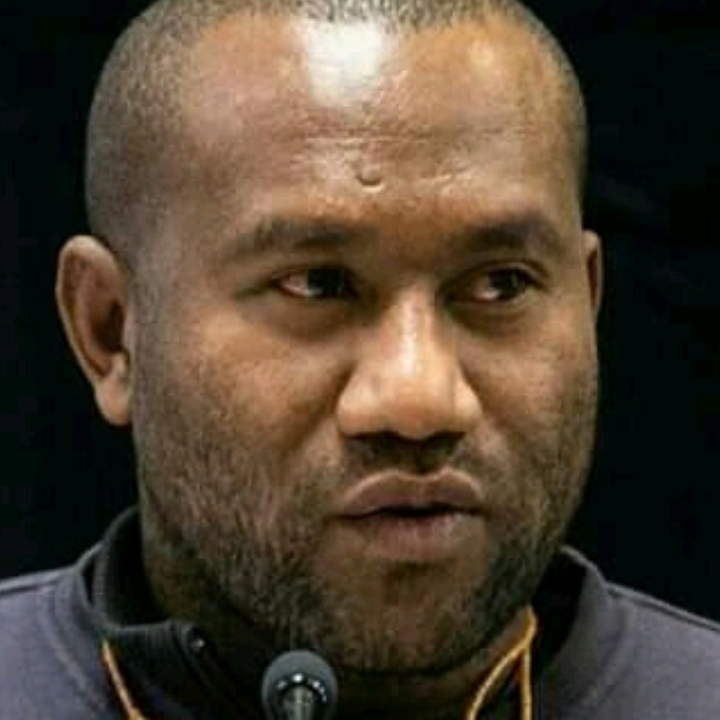

Interview with Jonathan Mesulam, Papua New Guinea (PNG).

BHRRC

BHRRC: What is your name and what is your role as a Business & Human Rights activist in Papua New Guinea (PNG)?

My name is Jonathan Mesulam. I am from New Ireland, PNG. I'm campaigning on issues relating to experimental deep-sea mining, climate change and logging in New Ireland. My role in the deep-sea mining campaign is to educate and advocate on the potential impacts of deep-sea mining on our coastal communities.

BHRRC: What are the human rights issues you are dealing with as a Business & Human Rights activist in connection with sea bed mining in PNG? How did you come to be involved in these issues?

Free prior informed consent; getting views from local people when a major project is proposed to their communities or villages is very important. All stakeholders either benefit from the project or are impacted by the project in some other way, so they have to be fully aware of what it will involve. The people must have complete information on any negative impacts the project may have on their livelihoods.

It is only when a project gets into full operation that the people become aware of the environmental destruction that they face. The culture is being destroyed as the plants and animals that they used to get for cultural activities are gone. And traditional medicines are also gone along with the sites where they collect them. When people are being affected by the pollution from mining or logging, then you also have a lot of issues like sickness. These are things that the people must be aware of, before a project starts.

Our culture is our identity. Culture, like the medicine, the dressing and the food, is important to our sense of who we are. When we lose all of those, we lose our culture. When people lose their culture, they lose their sense of community. Our community protects us from abuses and harms. We have respect for people in the community. When we lose our culture, people don't respect each other, and this sews disharmony in the community. Before these big projects came, people respected each other. Money that they get comes from the project, and they tend to use it on alcohol or drugs. Then a lot of problems come into the community from violence and noise from drunks. Community fighting becomes a community disorder.

I'm a teacher by profession. I've taught in primary and secondary schools. I began opposing deep-sea mining after seeing the community being fooled by companies operating in PNG and abroad. People have been misled thinking that when they bring this project, it's going to benefit everyone. But the local people tend to be vulnerable because they are not well educated. Most of the time, these educated people come and talk only about the good side of the project. They fail to mention the negative impacts that the project will have. When communities hear about the benefits, they think that the project is going to bring good, so they agree to it. When the project starts, though, the mining companies can fail miserably to fulfil their corporate social responsibility. Seeing this, I decided to leave teaching and advocate on this issue to educate people. I'm not stopping the project, but when I educate people with the full story, they start to realize that they are not being properly informed.

“We are all indigenous people. We lived in peace for tens of thousands of years without mining. We have had no big projects and needed no big projects. We have learnt to respect each other based on our culture, based on our traditions. We have to build regional solidarity on that basis in the fight to stop deep-sea mining.”

BHRRC: Why are local communities in PNG concerned about sea bed mining?

The minerals under the ocean were only discovered around 1977. We only have around thirty years of knowledge about the ocean floor, while the knowledge we have on land is closer to 40,000 years. New companies looking to engage in deep-sea mining have limited knowledge and understanding of how the sea bed operates.

Deep-sea mining is an experiment. There is no precedent you can refer to for understanding its likely impacts. We fear this project will have a huge impact on the local fisheries where local indigenous people fish. It may have an impact in the national economy for the same reason.

Deep-sea mining is also proposed for an area with active hydrothermal vents which could be dangerous. We are sitting right around the Pacific Ring of Fire—and the area is going to be mined? It might cause a tsunami. This is something that we are concerned about.

Deep-sea mining could affect the culture of the shark callers of New Ireland, the Barok and Mandak people. Sharks are very sensitive to sound, to noise pollution in the sea. Once those deep-sea mining machines start operating, they will scare the sharks, who will leave. Once we lose this, what are we going to tell the future generations—that we were once shark callers? As I keep pointing out, when we lose our culture, we lose our identity. This culture is very unique.

BHRRC: What has been the attitude of sea bed mining companies operating in PNG in engaging with local communities in terms of transparency and keeping them informed?

In my view, they failed to give enough information to the community. I've met with company people several times and told them we oppose you. Their attitude is that they will go ahead because they want to have this project.

BHRRC: Were local communities able to adequately raise their concerns with Nautilus Minerals?

People in the community don't know their rights, they don’t feel free to speak up. They feel that if they do speak up, they might become targets for repression. We found that if people were able to speak up, it was because we had helped them to know their rights and feel free to raise their voice by giving them factual information.

BHRRC: How are you approaching these issues, what are your strategies—what has worked well?

We educate people about the possible negative impacts. When they realise the truth about what may happen if deep-sea mining goes ahead, they start to react. The one thing I’ve come to realise over the time I've worked in the community, is the need for factual information. If the people know the facts, they have more power. It is our responsibility to give factual information to communities and to support them to speak up when they know something is wrong. By building networks with like-minded people and like-minded organizations, we can work together for the common good. We can seek information from partners and share information with them.

“When we are divided, companies take advantage of our division. We have to stick together.”

BHRRC: Tell us about the campaign and how it progressed. Who did you work with and how?

We have campaigned for the last seven or eight years. We have done forums, awareness campaigns, and made documentaries. We are very grateful to network partners that have supported us, not only in PNG but aboard—environmental NGOs, scientists, individuals like David Attenborough and journalists that are coming into the province.

Our political leaders do not support the people. In the provinces, our three members of parliament will not support us. They tell to wait and seem to be thinking about how they're going to benefit from the project. The majority of the people support us. It's people's power we tend to use. It's the people's power and the advocacy campaign by certain groups that convinces investors to pull out from the project. This is very important for us.

In 2017, we went to Fiji to present to the Pacific Council of Churches. In our presentation, we challenged them about the role the church has to play—not just locally, but for the region as a whole. We argued that in looking after the people, they have a role to play to save humanity. That was the challenge that the church received – to come on board and advocate on this issue. They provided strong support and played an important role.

We have a saying that there are three layers of the campaign—the local people, the regional groups, and the international organizations. They all have to stand up and contribute to the one message to ban deep-sea mining.

BHRRC: What challenges did you face in the campaign, and how did you overcome them? What kind of toll did the struggle against Nautilus take?

Financing activism is a big challenge. You cannot travel to a community to talk without paying for a bus. You have to raise those funds to enable mobility and communication.

The second major challenge is capacity building. We deal with that by sharing challenges; we then help each other and strategize in our workshops so that we can learn from each other. Networking helps with this a lot, and the support of partners like Bismark Ramu Group, Deepsea Mining Campaign, Caritas PNG, PNG Council of Churches and Mining Watch Canada is very important.

Some of the people in the community supported deep-sea mining, and this creates division. We have had to work hard at times to really convince the people that this project is not good. It's only through persistent, dedicated work and making information available so that people have all the facts, not just the perspective that the company wants people to know, that people will really support you. Once the people know the truth, then you get the support.

BHRRC: What is happening with the campaign against Nautilus Minerals now?

Nautilus has been delisted, but they still hold deep-sea mining licences. They could sell those licenses or form a new company to go back into operation. That is our biggest fear.

BHRRC: What would you consider the most important lesson from the campaign to pass on to others? What were the main reasons for its success and the biggest lessons for others working on these issues in the Pacific?

The important lesson is that we have to stand together with one goal, one message. You have to raise the same issue, involving different stakeholders, and do so in a way that everyone can understand. Building solidarity is very important to address the issue. When we all have the same message, when we all work together on the issue through solidarity, then we will be able to achieve our goal.